I share John McWhorter’s opinion about liberals’ attitude toward all-black or majority-black schools. Why are they considered some kind of tragedy?

I share John McWhorter’s opinion about liberals’ attitude toward all-black or majority-black schools. Why are they considered some kind of tragedy?

“We are meant to cringe at the sight of a photo of an all-black classroom and ask cynically where the white kids are,” he writes. “Oh, no one puts it just that way. But this is indeed the zeitgeist—one need only consider typical pieces on school re-segregation in our times, where the mere fact of black kids learning together is considered unfortunate and backwards, such as here and here.” Someone needs to shout this statement from the rooftops: “But the lawyers arguing Brown did not demonstrate that black kids need white kids next to them to learn better.”

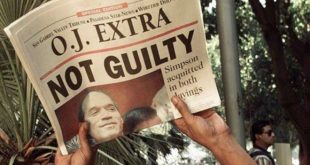

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) established legal segregation, and Brown v. Board of Education (1954) declared it illegal. Saturday marks sixty years since the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed government-mandated racial discrimination in schools. Shortly after the landmark case, the same court decided Brown II. Schools were ordered to proactively desegregate “with all deliberate speed.” The pace of integration proved too slow for social engineers, however, with their visions of an everybody’s-equal utopia.

Instead of allowing integration to proceed naturally, they used the courts to force their idealist vision. And, as McWhorter points out, they associated majority-black schools with tragedy. Beginning in 1968, the Supreme Court authorized forced busing. Without a single vote by the people, the court imposed unconstitutional policies in search of its “racially-balanced” fantasyland. Racial quotas would now be used to create this balance. Black and white students were shipped out of their neighborhoods to schools across town. It turns out parents didn’t like the government experimenting with their children. One of the unintended consequences was “white flight.” Urban schools began to decay as community tax bases shrank.

What people either forgot or didn’t know about the Brown case is plaintiff Linda Brown had to walk six blocks to a bus stop to ride to a black school a mile away, bypassing the white school closer to her house. The government said she couldn’t attend her neighborhood school because she was black. Her father, Oliver, brought the case to court to keep his daughter in her own neighborhood, not send her across town for “integration.” (These days, “neighborhood schools” is considered code for a return to segregation. Ironic.)

What would Brown-era children think about liberals’ attitudes today?

Blacks at the time of Brown brought into our present day would be baffled, and even irritated, by the idea that black kids are automatically worse off when white kids aren’t around. Long before the 1960s, and deep in the heart of Jim Crow, students at all-black Dunbar High in Washington, D.C., often outscored the city’s white schools on standardized tests as early as 1899—that is, when Plessy v. Ferguson of 1896 was a current event.

One of the many wonderful things about living in a country like the United States is people are free to live wherever they can afford. It’s not illegal to avoid living around certain people. Even liberals do it! I’ll go so far as to say it’s not immoral, either. Parents naturally want to live in low-crime areas with good schools, and those who can afford it do. But that doesn’t mean racism is the motivation. Even if it were, it’s not illegal to be “racist,” as long as you’re not violating anyone’s rights.

Unfortunately, the courts have re-introduced government racial discrimination in the form of racial preferences.

As you read stories with such headlines as “Still Separate and Unequal,” “Why Segregation Survives 60 Years After Brown v. Board of Education,” and “Moving Backward,” remember that today’s segregation is neither government-mandated nor illegal. It’s called freedom of association. (President Obama sends his kids to a private, majority-white school. Is he a racist?) And ask the “resegregation” alarmists why they believe a black student can’t learn unless he’s sitting beside a white student.

Part of this post was adapted from a previously published version on La Shawn Barber’s Corner.

Black Community News News and Commentary for Christians

Black Community News News and Commentary for Christians