After a series of high-profile events, such as tragic infrastructure collapses in predominantly black communities, policing killings, and a spike in urban violence, society is starting to place a greater emphasis on issues in the black community.

Although the responses to this rising interest in the black condition have been far from uniform, this issue of black advancement has become an increasing focus for many seeking to alleviate social inequities. We share the goal of building more prosperous black communities, but we believe that to be productive toward a desirable outcome for distressed black communities we need to address some common myths.

1.) Racial Political Representation Improves the Black Condition

To be clear, we agree with electing or appointing black men and women to positions of power when they have a proven ability to excel in the positions. We are strong proponents of meritocracy because we understand that advancing society requires talented people to create and produce. However, the link between racial representation and social equity is weak and unproven.

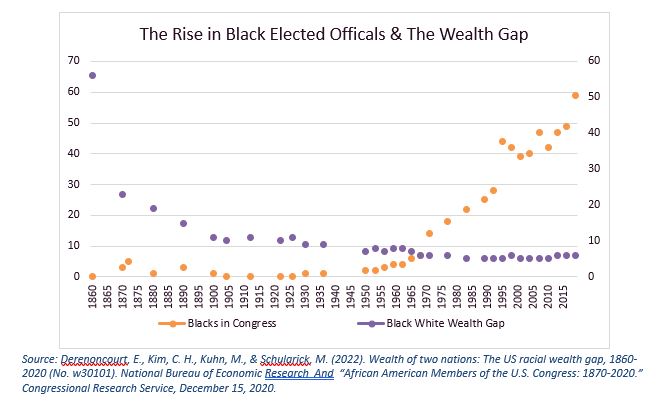

The chart above shows the number of black people in congressional membership on the right axis and the ratio of the white-to-black wealth gap (a lower number is properly interpreted as a reduction in the racial wealth gap). This data was compiled by combining a 2022 study on the white-to-black wealth gap, taking the per capita total assets of the white population, and dividing it by the total assets of the black population and by the Congressional Research Service data on black congressional membership in both chambers1 2 .

Although there were rapid gains after slavery (due to the fact that blacks were going from nothing to something) these gains slowed and failed to converge. Although the graph shows a substantial reduction from the immediate post-Civil War period it’s important to keep this in context. For example, the data shows that in 2019, black Americans held just 17 cents on average for every dollar of white wealth and the annual income gap was 50 cents to the dollar3.

A look at the graph above shows that, despite the lack of black congressional representation in Congress before 1965, dramatic reductions in the white-black wealth gap took place. Similarly, with a stark increase in black congressional membership the racial wealth gap remained mostly unaffected, and by some measure began to slightly increase in the 90s4. The goal of this information isn’t to attack black legislators as inadequate or ineffective; that would be unfair. All legislators should be judged on their individual performance by their respective constituencies regardless of race.

Admittedly this is a surface-level preview, there are more ways to measure black advancement than monetary gains. However, we feel this is an appropriate proxy for gauging the black condition for the current analysis because financial power is associated with a higher quality of life and longer life expectancies. Similarly, black congressional membership is a proxy for black political power in lieu of more comprehensive data. However, if anything, our graph likely underestimates the growth of black political influence. Partial data from the U.S. Census and Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies shows that from 1970 o 2001, the nationwide count of black elected officials grew from 1,459 to 9,061 and is likely more than 10,000 today5. It seems clear from the data that the relationship between racial political power and racial wealth equity is weak to non-existent.

Read the full report at CUREpolicy.org.

Raheem Williams is a policy analyst at the Center for Urban Renewal and Education.

Photo credit: COD Newsroom (Creative Commons) – Some rights reserved

CURE News and Clergy Blog News and Commentary for Christians

CURE News and Clergy Blog News and Commentary for Christians