When the United Auto Workers walk off the job, no one pretends that they are acting in the interests of car buyers. Everyone knows union members want better wages, benefits, working conditions and job protections, and going on strike is an effective way to exert pressure on employers.

When the United Auto Workers walk off the job, no one pretends that they are acting in the interests of car buyers. Everyone knows union members want better wages, benefits, working conditions and job protections, and going on strike is an effective way to exert pressure on employers.

The calculation is no different when teachers strike. Unions like the National Education Association, the American Federation of Teachers and their thousands of state and local affiliates exist for the same reason as the UAW: to advance the interests of dues-paying members. Yet striking public school teachers and their union representatives insist they are acting on behalf of the children. We’re expected to believe that the priorities of education workers are perfectly aligned with those of students.

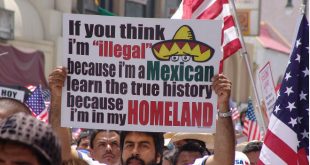

The Los Angeles teachers strike ended Tuesday after six days, and casual observers could be forgiven for thinking that the walkout was all about the kids. Union picketers carried signs that read, “On Strike for Our Students” and “Fund Our Schools / Give L.A. Students the schools they deserve.” A high-school teacher wrote in the Journal last week that he was striking for the sake of his charges: “As a teacher, my loyalty is to my students. We’re fighting this battle for them, and they will be the victors.” In a paid advertisement in Sunday’s New York Times, AFT President Randi Weingarten used similar language. “Everything teachers are demanding would strengthen public schools,” she wrote. The strike is about “ensuring that all public schools have the conditions they need for student success.” Yeah, right.

Before the Los Angeles strike began, local officials took steps to keep schools open by hiring substitute instructors and aides. The striking teachers did everything they could to sabotage those efforts, like taking textbooks and supplies home to ensure that they weren’t used during the strike. That’s an odd way of looking out for the interests of your students.

Ms. Weingarten’s reference to “all public schools” is misleading. She really means all public schools that employ union members. Public charter schools, which are mostly nonunionized and growing rapidly in the city, don’t count in her estimation. Charters now enroll about 20% of public school students in Los Angeles, up from 12% seven years ago, and curbing the expansion of schools that don’t employ their members has long been a major priority of teachers unions. The Los Angeles Times reports that only 42% of the district’s students can read at grade level, and math proficiency is an even lower 32%. Families are fleeing union-run schools, so labor leaders are trying to block the exits. Whether students benefit from more school choice is not something that concerns teachers unions. They care whether their members benefit.

Los Angeles teachers were following a path blazed last year by educators who demonstrated in places like Arizona, North Carolina, West Virginia, Colorado and Washington state. They demanded bigger budgets, higher salaries, smaller class sizes and less standardized testing. Put another way, they want more pay for less work and accountability. Gee, who doesn’t?

For teachers, reducing the size of each class means fewer children to mind and assignments to grade. For unions, it means more jobs for dues-paying teachers and ultimately more money in AFT and NEA coffers to spend lobbying politicians and policy makers to keep schools organized in a way that benefits their members first and foremost.

The union has won some concessions on pay and class size, but whether the deal will improve test scores, graduation rates or college readiness is an afterthought for labor leaders. And we have every reason to believe it won’t. The U.S. spends more than twice as much on education—per student and after inflation—as it did in 1970 and more than three times as much as in 1960. School expenditures in high-poverty districts are typically well above the national average.

Yet standardized test results show little improvement, and large racial gaps persist. We’ve long known that class size matters much less than teacher quality. Charter schools with larger classes have outperformed traditional public schools with smaller classes. And in countries such as Japan and South Korea, which regularly outperform the U.S. on international tests, average class sizes are larger than here.

Teachers unions are unions first, not reformers or student advocates. Their real agenda—their only agenda—is to protect their members by any means possible. No matter what those picket signs said, the unions weren’t helping students. They were using them.

Photo credit: San Mateo (Creative Commons) – Some rights reserved

Jason Riley is a member of The Wall Street Journal Editorial Board.

Jason Riley is a member of The Wall Street Journal Editorial Board.

The views expressed in opinion articles are solely those of the author and are not necessarily shared or endorsed by Black Community News.

Black Community News News and Commentary for Christians

Black Community News News and Commentary for Christians