Fifty years ago this weekend, a deadly urban riot began in Detroit. It started around 3:30 a.m., when police arrested 85 patrons of a blind pig — an illegal after-hours bar — in the midst of an all-black neighborhood that had been all-white 15 or 20 years before.

Fifty years ago this weekend, a deadly urban riot began in Detroit. It started around 3:30 a.m., when police arrested 85 patrons of a blind pig — an illegal after-hours bar — in the midst of an all-black neighborhood that had been all-white 15 or 20 years before.

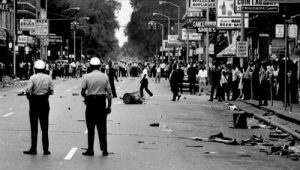

The statistics are horrifying. Rioting went on for six nights, with some 2,500 stores looted and burnt, some 400 families displaced and property damage was estimated around $300 million in 2017 dollars. Forty-three people, many of them innocent bystanders, were killed. More than 1,000 people were wounded.

The reality was even more horrifying. That summer, I had wangled a job as an intern in the office of Detroit Mayor Jerome Cavanagh, a young, bright and ambitious liberal. Elected with near-unanimous support of black voters, he had aggressively launched anti-poverty programs, trying to make the nation’s fifth largest municipality a model of the Great Society’s War on Poverty.

He had not succeeded, however, in changing the modus operandi of a police department that was only 5 percent black in a city with a 38 percent black population. In retrospect, this was a tragic consequence of the migration of one-third of American blacks between 1940 and 1965 from the mostly rural South to the big cities of the North.

That meant that Detroit, which had about 150,000 black residents before World War II, had about 600,000 a generation later. At a time when almost no whites would remain in neighborhoods with a significant black population, and when there were significant differences in the mores and culture of blacks and whites, this was inevitably going to be problematic.

Notwithstanding Cavanagh’s liberal policies, and those of Michigan’s Republican Governor George Romney, the riot should not have been the surprise it was. If it was more destructive than the riots in so many other cities, well, Detroit was bigger than just about all those other cities and had had a larger influx of Southern blacks than all but Chicago and New York.

I arrived at the City County Building on the warm morning of Sunday, July 23, and spent the next six nights at work. Unfortunately, I made no notes at the time and so my vivid memories may not be entirely accurate. But they show how fragile the web of civilization can be, just as what happened to Detroit over the next decades show how difficult they are to repair after they’re torn to shreds.

I remember listening after sundown in the police commissioner’s office to the police radio, as one officer after another reported abandoning another neighborhood — whole square miles — to the rioters. I remember the mayor, concerned about the trigger-happy performance of National Guard troops, trying to persuade the governor to demand federal troops from a reluctant President Lyndon Johnson and Attorney General Ramsey Clark.

I remember riding around in a (nonpolice) car with Congressman John Conyers, then in his second term and now the senior member of Congress, as he told young black men to cool it and stop the violence.

After several days, the experienced (and not all-white) 101st Airborne came in and calmed the city down. Johnson summoned the Kerner Commission, which blamed the Detroit riot on white racism and called for massive federal spending to somehow overcome it.

What followed was the cycle of vastly increased violent crime and welfare dependency that nearly tripled in the 1965-75 decade and was not reversed until the 1990s. White flight reduced Detroit’s population from 1,670,144 in 1960 to 1,027,974 in 1990; black flight reduced it from that to 713,777 in 2010.

It has become the fashion to call the Detroit riot a “rebellion,” though it was not premeditated and had no explicit policy goals. It was the product of expectations combined with a certain understandable discontent. People throw bottles, break windows, loot stores and set fires when they think that enough other people will be doing the same as to make them immune from punishment.

Riots in American cities proliferated from Los Angeles’s Watts in 1964 to the multiple riots following the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. They have been rare in the 49 years since; the 1992 Los Angeles riot ended after 18 hours and the dispatch of 25,000 federal troops — more than double the number in Detroit.

Lessons learned these last 50 years: Riots hurt, not help, people like the rioters. Riots can be stopped, and prevented, by authorities willing to deploy overwhelming force.

COPYRIGHT 2017 CREATORS.COM

Michael Barone, senior political analyst at the Washington Examiner, (www.washingtonexaminer.com), where this article first appeared, is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a Fox News Channel contributor and a co-author of “The Almanac of American Politics.”

Michael Barone, senior political analyst at the Washington Examiner, (www.washingtonexaminer.com), where this article first appeared, is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a Fox News Channel contributor and a co-author of “The Almanac of American Politics.”

The views expressed in opinion articles are solely those of the author and are not necessarily either shared or endorsed by Black Community News.

CURE News and Clergy Blog News and Commentary for Christians

CURE News and Clergy Blog News and Commentary for Christians

A huge difference between the riots of Detroit and Chicago is that Detroit Police and the National guard were ordered NOT to shoot rioters (the National Guard was not even issued live rounds) while Chicago PD WAS ordered by Mayor Daley to shoot rioters. Chicago’s riot was over within 48 hours with a total 11 dead and has primarily recovered. Detroit had, over 4 days, 43 dead, 1,189 injured, over 7,200 arrests, and more than 2,000 buildings destroyed. The ramifications of Detroits riots are ongoing to this day.